Disclaimer: I am long shares of Distribution Solutions Group

Introduction

Distribution Solutions Group is an industrial distribution business that operates globally offering distribution of over 400,000 distinct SKUs to MROs and OEMs. DSGR sources and re-sells an abundance of class C parts such as adhesives, fasteners, screws, nuts, washers, gloves and test and measurement equipment from over 120,000 suppliers to 6,000 customers. Despite serving multinational companies such as Apple, Boeing, Lockheed and Broadcom I estimate that no customer makes up more than 5% of revenue.

DSGR is a holding company formed through a reverse merger of two PE owned distribution businesses (Gexpro and TestEquity) with Lawson Products, previously a public traded company under LAWS, in April 2022.

Through the Lawson segment (27% of revenues) they provide vendor managed inventory (VMI) services and distribute class C parts such as fasteners, washers, cutting tools, specialty chemicals and aftermarket automotive supplies to small maintenance, repair and operations (MRO) shops in various industries such as manufacturing, automotive and government/military.

Lawson has separated themselves from both large and small distributors because of their VMI focus. The VMI go to market is heavily service-focused which allows for 90% customer retention and gives Lawson pricing power to preserve 50%+ gross margins.

Gexpro Services (23% of revenue) has a similar offering to Lawson. They provide VMI services and distribute class C parts to large OEMs. Customer concentration is much greater at Gexpro compared to Lawson, but because of their more complex operations customer retention is also higher at 98%. However, because of the more concentrated purchasing power large OEMs have compared to small MRO shops, Gexpro exhibits 20% lower gross margins than Lawson.

Lastly, TestEquity (50% of revenues) provides test and measurement equipment distribution to the aerospace and defense, industrial electronics and manufacturing and semiconductor production markets. This business split is between service and distribution. Distribution is lower margin and has lower barriers to scale so companies compete on price. Hence, TestEquity is growing its service focus both organically and inorganically which is an inherently stickier offering due to the routine calibration needed of the equipment they sell and allows for 6-8% higher gross margins vs distribution. This leads to structural margin expansion in the business.

Most of the products sold by DSGR's operating companies are mission critical (the OEM and MRO shops can’t run their business without parts) and clearly a small share of the total customer wallet, which makes for stickier customers – why switch your distributor who has the parts you need and risk something going wrong? DSGR can also stock lower turnover/rarer parts that small competitors can’t store and embed themselves through VMI, which contributes to higher switching costs. Finally, it’s worth noting that DSGR is leaning in toward stronger end markets such as automotive, A&D, medical and government/military.

Scale economies have allowed DSGR to take share from the long tail of local mom & pops. Scale allows DSGR to have greater route density which lowers costs to serve per customer (because they can get to more customers per day), increases bargaining power over suppliers, improves the segments’ ability to cross sell services and reduces lost sales through a wider breadth of SKUs. The combined entity’s broader geographic reach allows them to service national and multinational clients cheaper by consolidating their spend.

Mom & Pop distribution businesses often do not have the workforce to roll out as deep a service offering which hurts pricing power and forces them to operate at structurally lower margins. DSGR’s scale allows them to have a separate procurement and service function which increases the level of service customers get from DSGR. Sales reps can focus on specific verticals and get a feel for local market dynamics that a mom and pop servicing only a handful of customers can’t.

Beyond price, customers care about the distributor having an item in-stock for immediate delivery and saving customers time. Distributors hold inventory so that customers do not have to, which frees up working capital for its clients– an important factor in cyclical businesses such as manufacturing. Local players are much more balance sheet constrained and can’t offer the same benefit. Local density and a deep breadth of SKU provides for significant operating leverage over a fixed-cost base which allows scaled distributors to achieve attractive 20%+ returns on invested capital.

As DSGR scales, many of their competitive advantages build on each other. In particular, as DSGR acquires more distributors they can cross sell services to customers and increase their share of wallet. E-commerce is probably the largest external risk. The convenience of sourcing online with an endless assortment of SKUs is compelling. However, DSGR differentiated themselves through their high touch service offering.These multi-million SKU ecommerce offerings compete on selection and price, catering to large customers. DSGR’s service focus has allowed them to better serve the small and mid sized business segment while preserving margins. They focus on providing value to customers.

As a result, I think DSGR is well positioned to continue taking share from small competitors for years. Other distributors like Fatsenal and Grainger are building out their service offerings, but the market is large enough that each can focus on displacing local distributors for decades.

On capital allocation, the DSGR platform also opens up opportunities for a long runway to redeploy capital via M&A by acquiring other small distribution businesses and leveraging scale economies.

Lastly, I view management very positively. Equity ownership amongst the management team is astoundingly high. The operational management team at DSGR is quite strong.. Bryan King was appointed CEO after the reverse merger and is taking no compensation as CEO or Chairman of the board. All of his compensation comes from his family’s 20% ownership of the business. He has been allocating capital in the distribution industry for two decades through PE and is focused on creating value for “shareholder partners.”

Thesis

Lawson Products has undergone a transformative transaction from a subscale, sub-$500mln market cap company with little reinvestment runways $1.7B+ specialty distribution holding company with a heavily invested majority shareholder who can grow EBITDA organically low to mid teens over the next few years. Going forward, DSGR will have a more robust set of acquisition opportunities (already demonstrated through the pace of deals since the reverse merger) where cross-selling and cost synergies can deliver low double digit EBITDA margins fueled by 25% incremental EBITDA margins.

There are a handful of bear points that on their own are small, but accumulated lead to a mispricing and some debate. DSGR recently announced the acquisition of Hisco for $269.1m. The deal will be done through a mix of equity (a 2.22m share rights offering at $45 and $170m of debt). The sell side is mis-modeling the impact of Hisco on both the go-forward organic growth rate of the combined TestEquity and Hisco businesses and the improved margin structure as Hisco has higher gross margins and will be accretive to EBITDA margins post synergies.

There is also the perception that industrial distributors are over earning as commodity inflation has been largely positive to GM dollars, but that normalized operating margins are only mid single digit. I think this criticism discounts management’s ability as operators, the stickiness of the pricing they are able to pass through their services and the benefits of scale that DSGR is beginning to realize. In a recession, organic volume growth will likely go negative, and the company will appear more expensive as earnings are temporarily depressed and leverage will increase from an already peer group high of 3.5x.

As a rebuttal, significant cash will be released from working capital and the sudden glut will fund high ROIC M&A at the perfect time and help deleverage the company. DSGR’s variable cost structure and embedded services with 90%+ customer retention help protect margins in downturns. In the long run, the high touch distribution market is $57b and growing 2-3% per year which provides a backdrop for DSGR to grow 2x GDP organically with upside from tuck in M&A.

Not only should DSGR be able to reach new customers, but they are also well positioned to increase their wallet share through cross selling new services and SKUs. In addition, VMI services result in sticky customers, who are demonstrably less price sensitive. Integration efforts have proved fruitful with EBITDA margin expansion and an increase in organic volumes.

At the margin, DSGR’s short life as a public company and controlling shareholder reducing free float/liquidity also play a role in why this opportunity exists. Pro forma for the Hisco acquisition DSGR will be a $1.65b EV entity that does $190m in EBITDA. Indicating the company trades at at 8.6x EV/EBITDA. I believe this is too cheap for a business that has 25% incremental EBITDA margins growing EBITDA low double digits per year run by an aligned and engaged private equity firm that owns 77%. As the company continues to deploy capital in attractive M&A and successfully integrates recent acquisitions with both revenue and cost synergies, I believe the market will price DSGR more in line with other industrial distributors in Exhibit B.

I believe that DSGR is worth $72.00 per share in my base case, representing a 59% upside from the current share price. Looking out to12/31/2027 exit I value the Company on $360m of NTM EBITDA at an 13.0x multiple for a total enterprise value of ~$4.68bn, an equity value of $3.4bn, and FDSO of 24.8mm for a target price of ~$138 and an IRR of 27%. Albeit dated, precedent transactions such as Barnes Distribution North America were done at 13x EBITDA and smaller peers have fetched mid teens. 13x would represent a return to Lawson’s historical valuation when it was less liquid and had worse unit economics. A capital light business in a massive industry, consumable nature of its products, high gross margins and the low churn of its customer base, Lawson and Gexpro deserve solid multiples on their cash flow. TestEquity’s closest comp in public markets is Transcat which is undoubtedly a superior business, but trades at 23x EBITDA. Marking TestEquity at 13x is conservative if not overly punitive.

As always you can access my model below and feel free to reach out with feedback.

Background

In April of 2022, Lawson completed the reverse merger that combined it with Gexpro Services and TestEquity, two distribution businesses previously owned by Luther King Capital Management (LKCM). All three niche industrial distribution companies were brought under a holding company each operating independently with their existing management teams heading separate divisions, but sharing best practices, product lines and distribution scale economies.

DSGR operates with a decentralized structure. The operating businesses keep their brand names and have their own management, but the cash is upstreamed to the holding company. The three operating companies can be more responsive and tailored to customers while flexing the balance sheet of three combined entities. This shows up in higher than industry-average volume growth of 3-5% because of the performance focused culture and higher customer loyalty with lower churn.

Prior to the merger, Lawson had historically been a sub $500m market cap, subscale VMI business (demonstrated by anemic EBITDA margins and a flat stock price from 1999-2017) with only 4 regional distribution centers. The business chugged along and acquired a few other brands such as Partsmaster’s, Bolt Supply House, which serves customers in Western Canada through several branch locations and Kent Automotive, where they provide collision and mechanical repair products to the automotive aftermarket, but struggled to get any institutional attention (only 2 sell side analyst covered the name for years). LKCM, who owned 48% of Lawson prior to the merger, realized that there were limited avenues to redeploy capital within Lawson and that the business could be improved through scale.

The transaction took Lawson from a company that did ~$20m in EBITDA in 2021 to more than $120m in EBITDA in 2022. Gexpro and TestEquity reduced seasonality and cyclicality at Lawson by diversifying end markets taking total customers from 90,000 to >120,000 which allowed management to more confidently lever the business. As a standalone entity, Lawson was consistently near 0 net debt, but DSGR management has taken this up to a target range of 3-4x which allows the combined entity to pursue accretive M&A. The M&A firepower of the entity can be seen in the stark contrast in the pace of deal at Lawson pre merger compared to DSGR’s short time as a combined platform. Since 2015, Lawson has completed seven acquisitions solely focused on MRO VMI segment. However, the identification and completion of acquisitions in this sub-market of the larger fragmented MRO market has become more challenging given the limited number of meaningful acquisition targets available. Through DSGR’s broader vertical, management has been able to redeploy cash generated by Lawson’s into 6 since the merger in 2022.

In addition to growing the M&A pipeline that should allow for a much longer reinvestment runway, the DSGR combination allowed for significant economies of scale. Exhibit C shows Lawson’s and Gexpro’s adj. EBITDA transformation as a result of the merger (which occurred in Q2’22). This improvement is a result of route density, increased purchasing power, consolidated back office resources and acquired sales reps at Gexpro selling Lawson private label product lines at higher gross margins than manufacturer-branded lines. Class C parts such as washers, fasteners, tools and hard hats have a very high weight to value ratio which makes them very expensive to ship. So, having dozens of geographically disparate facilities should lead to reduced transportation costs at the margin if DSGR can shift volumes effectively between DCs.

The margin improvement also offers anecdotal evidence of management's ability to not only identify, but also capture cost synergies for future acquisitions. The combined entities also are better able to cross sell combined products and services and capture a higher share of wallet with SKU expansion. From 2011 through 2021 Lawson sales grew at a 2.2% CAGR including M&A. Because of the low inflation during this period I think it is fair to assume that this can be used as a proxy for volume growth in the business. Since being acquired in Q2’22 DSGR has disclosed that Lawson volumes are up between 4-5% over 2021 showing clear signs of the ability to increase organic growth via cross sell/greater wallet share. Doing some guess work to strip out the impact of inorganic growth from M&A from Gexpro’s quarterly results you can see quarterly improvement in sales pre and post merger. Management disclosed low double digit (10-13%) pricing at Gexpro in 2022. Revenues were up ~15%/y/y in 2Q22/3Q/4Q and up 8% in Q1’23 which implies healthy volume growth of 2-5%.

Cross pollinating services increases customer switching costs and should help reduce churn/improve net organic growth at both businesses. If integrated properly, acquired business should be able to approach existing customers with solutions that include products and services from the other DSGR subsidiaries. Cross selling takes longer to implement than cost synergies so tracking volume growth going forward is important in order to measure progress.

When the deal was first done there were governance concerns around LKCM selling two portfolio companies to a 48% controlled entity, but LKCM (and its affiliates) chose to solely receive DSGR stock in the deal and increase its ownership to 77%+. In effect, LKCM who have been terrific operators of distribution businesses for decades took 0 cash out of the transaction and are taking 0 board fees going into the future so their sole compensation is based on the stock working.

Intro to Distribution Solutions Group

DSGR is a specialty distribution company providing high touch, value added distribution to the maintenance, repair and operations (MRO), OEM and industrial technology markets. DSGR reports in four operating segments: Lawson (formerly publicly traded under LAWS), TestEquity, Gexpro Services and All Other.

At the national level, scale results in better positioning when negotiating with suppliers, but at the local level increased route density means lower cost and more timely service. There are shades of a flywheel wherein as DSGR increases sales personnel they can serve customers faster and give customers better service which strengthens the relationship, reduces churn and increases wallet share (i.e. penetration).

Lawson (~27% of pro forma revenue) serves customers via a high-touch, customer-focused model of Vendor Managed Inventory (“VMI”) for low-ASP ($0.90), high turn consumables (fasteners, abrasives, adhesives etc). This value added service model goes beyond simply providing the part. One of Lawson’s 1,000 sales reps visits customer warehouses and plants (which there are over 90,000 distinct customers) on a weekly or more frequent basis where he or she will unpack the boxes, put the product away and place an order to replenish the inventory.

Lawson's customers include a wide range of purchasers of industrial supply products from small repair shops to large national and governmental accounts. Their largest customer accounts for approximately 3% of consolidated revenue and they source from ~2,400 suppliers with no single supplier accounting for more than 6% of these purchases. Clearly, Lawson serves a diverse supplier and customer base which lowers negotiating power on both ends and makes the cash flow stream more durable through reduced revenue cyclicality. I wouldn't have the chutzpah to call it recurring but the consumable nature of the class C parts makes the revenue stream stable. The need for a distributor arises because the skill required to produce fault-free Class Parts at high enough volume for it to be profitable differs from those needed to run a global supply chain that can reach the fragmented customer base. Individual suppliers face difficult logistical complexity and a lack of scale benefits if they try to go to market directly.

One of Lawson’s largest end markets is the resilient, underpenetrated and highly fragmented auto repair/body shop business where they have grown MSD. These customers care about time and convenience, the repair technicians usually charge their customers based on predetermined hours of labor, even if they end up finishing the job in fewer hours. Because these cars take up space in a shop, the quicker the technicians can finish a job, the quicker that space is freed up for the next job. While Lawson’s products are less cyclical due to their consumable nature, they are still tied to industrial demand (if you use the machines less, you consume fewer parts). In 2015, despite oil and gas headwinds sales only fell 4% in the segment and EBITDA margins were flat from. The same is true from 2019 to 2020 when sales fell 5% and EBITDA margins expanded 40bps. Notice in Exhibit D that EBITDA margins are stable despite the volatility in sales highlighting the variable cost structure.

Gexpro Services provides VMI and supply chain services to manufacturing OEMs. They provide these OEMs with lower procurement costs for Class C parts. Gexpro serves almost 1,800 customers in over 38 countries through its 30 facilities. Their VMI services have over 100,000 installed bins which creates a stable base of customers. Gexpro has disclosed that ~65% of revenues in 2022 were from customers under long-term agreement which I presume to be greater than 1 year demonstrating stickiness and revenue visibility.

While Gexpro sources from a fragmented supplier base of 2,700 distinct suppliers (the largest supplier represented ~2% of total product purchases, while the top 10 suppliers represented ~15% of total product purchases in 2022); they have noticeably lower gross margins than Lawson. This is a result of their more concentrated customer base (OEMs as opposed to MRO shops) which implies that large customers have much more negotiating power. One customer accounted for ~19% of Gexpro’s total revenue in 2022 while the top 20 customers represented approximately 63% of Gexpro Services’ 2022 total revenue.

TestEquity is a test and measurement distributor for the aerospace, defense, automotive, electronics, education and medical industries. They design, rent and sell a full line of environmental test chambers, calibration, refurbishment and rental solutions and a wide range of refurbished products. Over the last few years, TestEquity has built out its product offerings (increasing SKU count and ecommerce presence) and now operates primarily through five distribution brands: TestEquity, TEquipment, Techni-Tool, Jensen Tools and Instrumex and serve over 30,000 customers sourcing from 1,050 suppliers. These brands together increase scale so they can shorten delivery time and now offer over 180,000 SKUs which has allowed them to build out their ecommerce offering which is 14% of sales and growing.

They have stumbled over the last few years because of a poorly executed ERP implementation, but seem to be recovering well establishing relationships with suppliers such as Keysight, Tektronix, Keithley, Kester, Desco, and Chemtronics. Their top 5 suppliers make up ~50% of purchases and Keysight Technologies is their top supplier at10%. They are rapidly adding suppliers (Keysight has fallen from 20% to 10% from ‘21-’22) and I have heard that there is "zero chance" Keysight moves away from TestEquity due to the channel adding significant value. Large manufacturers have tried to go direct in the past, but have failed due to a lack of inventory and not offering a service component indicating that the test and measurement side of the business (60%+ of revenue) has a competitive advantage through technical expertise. They employ over 100 domain experts to advise customers such as Google, Facebook, Boeing, SpaceX, Medtronic, Broadcom and Lockheed.

End users of the equipment are required to have it calibrated periodically which leads to recurring demand. The largest customers will have in-house calibration labs, while others rely on the OEM. A 3rd party provider such as TE or Transcat ‘s(TRNS) value add is that they service equipment from multiple manufacturers whereas an OEM would only work with their own product. In-house labs are becoming less prominent as end-users may not want to distract from their core business or are facing labor shortages. Transcats service revenue gross margins are growing faster and are 7% higher than distribution gross margins indicating some value add.

On March 31st, DSGR announced that TestEquity would acquire Hisco for ~$269m or 9.4x EBITDA excluding synergies. All of TesEquity’s acquisitions have been in the name of scale (the full benefit of which I’ll expand on below). Customer density is critical as it lowers transportation costs and maximizes the utilization of technicians. There is a whole slew of value added services that Hisco offers such as custom fabrication, packaging /labeling, clean room storage, labeling/printing and VMI. Hisco also deepens TestEquity’s reach into Mexico/Latin America/ and I suspect that there will be both cost and revenue synergies through cross-sell opportunities, footprint optimization and general scale economies which will allow them to cheapen the multiple to the low 7s or a solid mid teens ROIC. Management has said that they expect Hisco to accelerate the timeline to higher structural margin profile and increase organic revenue at TestEquity as well.

From my understanding Gexpro and Lawson were rather similar businesses that had imminent/obvious low hanging fruit and TestEquity, which was less VMI focused with more T&M exposure, was an odd man out of sorts. The Hisco acquisition solves this and bridges the gap between TestEquity and the other DSGR operating subsidiaries because it offers similar products to TestEquity, but has a similar go to market as Gexpro and Lawson.

The below-average churn rates and increasing ROIC indicate that DSGR has some competitive advantages. I think these boil down to DSGR’s emerging scale and a focus on a services heavy GTM. The combination of which has allowed them to steal significant market share from mom and pop operators who have been the largest share donors over time. The diversity in verticals and fragmented customer base also insulate cash flows.

MRO Industry Dynamics

The MRO (maintenance, repair and operations) market that DSGR competes in is large and fragmented. While estimates depend on the specific end markets each distributor serves, industry players such as MSC Industrial estimate that the North American MRO market is $215b, Grainger laid out a $165b addressable market and Fastenal estimates they serve a $140b addressable market. While like most (all?) TAM estimates these are finger-in-the-air, they point to the fact that the market is vast. It is also growing 2-3% per year through a combination of price and volume providing head room for DSGR to grow without directly competing with national talent. There is some volume growth from secular trends of complexity in hardware and onshoring and distributors generally pass along the input cost inflation. I feel confident underwriting that the industry can grow in line with GDP over the decade and believe that the numbers of class c parts used in manufacturing will be higher in a decade than what it is now.

DSGR has estimated they serve a $57b market which is noticeably more focused than larger peers as result of their high-touch vendor managed inventory (VMI) offering. Each individual reporting segment at DSGR serves a distinct addressable market. Management estimates in conjunction with TTM revenue numbers implies that Lawson, Gexpro and TestEquity has 2.5%, 1.3% and 5.7% market share in their respective markets.

MSC has disclosed the number of competitors in the market and market share of the top 50 distributors for the last 8 years, during that time the number of competitors has risen from “less than 140,000” to 145,000 and the market share of the top 50 has increased from less than 30% to 33% today. The remaining 67% of the market is made up of small local players who are attracted to the business because it is highly cash generative and relationship driven. This indicates that while barriers to entry are low (intuitively this makes sense: there is little technical know-how needed to buy nuts, bolts and fasteners and resell them at a markup so new competitors constantly enter the market), the large regional/national players are taking share from local mom & pops. Exhibit E shows that the largest North American players such as Grainger and Fastenal command between 2%-5% market share, there is a long tail of local players.

DSGR exists in an advantageous middle ground between the large distributors and local mom & pops. Large distributors enjoy economies of scale via route density and SKU depth/breadth over local players which allows them to serve large customers more effectively. Small customers with less than 10 employees make up 97% of customer count in the industry, but only 35% of the MRO revenue pie. On the other hand, medium to large businesses with >50 employees make up the remaining 3% of customer count but 65% of revenue.

Large distributors are uniquely advantaged to service these scaled customers and take revenue share from mom & pops for three reasons. First, national players can have greater product depth and breadth within the end markets where it focuses, including those that turn over at a slower rate. This not only ensures that customers can access even rare products on short notice, but also that sales reps will have greater technical expertise to serve the customer. This is a more underappreciated benefit of a scale advantage. Sales reps are able to spend a significant amount of effort and resources on becoming domain/customer experts, which helps them better serve customers. Reps can spend time learning new services or about new products which are more tailored to customer needs.

Many of the largest customers (The Boyd Group, Boeing, Broadcom, Apple) need a wide array of parts. Small manufacturers can’t make every single component themselves, but DSGR can stock and deliver it all. They can source an entire product line, which is compelling for large buyers. Once DSGR is supplying an entire product line of screws, metalworking and adhesives, I suspect that customers are less likely to switch to another distributor or multiple distributors.

Scaled distributors can offer fast, on-time delivery with lower prices because of local density with national logistics and inventory infrastructure to meet same-day delivery demands of customers who need parts on short notice. Delays in delivery lead to days of customer downtime which lead to lost profit for those manufacturers and construction firms. At the margin, customers would rather not spend 1.5-2 hours of the day driving to the local hardware store, Home Depot or Lowe’s (which often doesn’t carry many of the specialized parts needed) to shop around for little or no cost savings. Time and convenience matter. Therefore, we should expect to see that margins increase with scale. Exhibit F shows the relationship between revenue and EBITDA margins for the peer group. The correlation somewhat holds true at the low end of revenue but it breaks down with the largest players. Scale economies exist up to a point. The primary reason for this is that the larger the distributor the more they cater to large customers that have greater negotiating power which caps margins or in some cases reduces them. It turns out, that there are diseconomies of scale when a distributor becomes too large and can no longer service a fragmented base of small customers. There exists a happy medium that Fastenal seems to have found, and I’d argue DSGR is looking for, where absolute sales dollars are traded for preserving margins through a high service value add. The culture of leading with service and the logistics to effectively do this are barriers to scale small distributors don’t have the resources to manage hundreds or thousands of relationships with small shops.

High Touch VMI

For the procurement department of large customers the value proposition of a single provider that can reach your entire region or country makes sense, it could quickly become a headache tracking all the orders from dozens of different distributors for class C parts that sell for less than a dollar. We see this dynamic at Gexpro, which serves large OEMs, which has 98% revenue retention indicating that churn decreases as customers concentrate their spend. For contrast, Lawson’s focuses on MROs with 1-30 employees and has 90% revenue retention.

From the customers I have spoken with and expert call transcripts I’ve read it is difficult to overemphasize the power of personal relationships in this business. There is both a convenience and opportunity cost factor in switching. Switching costs also increase as wallet share increases which is why DSGR has focused on cross selling between the three operating companies.

Seeing the same rep every week (or more) is much more powerful than ordering from a catalog out of a centralized call center. Since Amazon and other online platforms have started selling industrial parts, transparency around pricing has put pressure on gross margins for the industry. Customer accounts are won (and lost) by the sales team pitching a service that online catalogs can’t offer. Small businesses with less than 50 employees tend to make their decision based on price because of the simple nature of their transactions and the commodity nature of the product itself, but DSGR’s VMI focus is more service based which shifts their customer focus from price to value.

Lawson is the quintessential example of the strength of a VMI go to market within DSGR. Lawson’s VMI focus has allowed them to preserve pricing and therefore gross margins over time as they lead with their VMI offering. The main selling points are that the customer is able to get the parts they need in an almost just-in-time fashion, Lawson sales reps act as outsourced inventory or procurement staff and the customer gets some balance sheet relief through lowering working capital.

In a sense, reps become part of the staff at customer locations where their job is to maintain an optimal amount of small parts inventory to keep the shop running, cut down on unnecessary working capital for customers and reduce overall cost of procurement. Reps add value by eliminating dead inventory, reducing search time for parts, reducing maintenance downtown (obligatory: “you’d hate to have your multi thousand dollar machine down for a few hours because you’re out of a $0.15 screw” comment) and increased material storage space capacity. Exhibit G (in the most microcap presentation of all time) shows the clear value add of a Lawson sales rep. I also think Lawson is currently benefiting from a greater need for their business as many of their customers are increasingly short labor and have gained a greater appreciation for the outsourced service from the Lawson sales rep.

Because many of the parts that Lawson supplies are low ticket items, convenience and procurement services can overcome price as a factor in purchase decisions. The actual parts necessary are typically a small percentage of the overall cost of a VMI job, i.e. labor cost greatest component of the total, service-geared distributors at scale have a tendency to pass pricing through "friendly middlemen" to end users which gives Lawson better pricing power than peers because of deeper switching costs.

VMI heavily leans on personal relationships and constant customer contact for small purchase items, which are delivered quickly (saving time and effort), and so being 10-20% lower priced won’t matter. For example, a Lawson or Gexpro rep may visit a job site and make sure all the part bins are full, keeping the job site running and reducing effort, which adds a service and convenient component which can’t be replicated easily. Whether parts cost $20 more than Amazon online just doesn’t matter for someone who is either cost plus, doesn’t care about small spend which doesn’t move the need, or just wants to keep things going. With this go to market strategy, Lawson has been able to retain a significant premium to Amazon in terms of price. Exhibit H shows Lawson’s remarkable stability in gross margin over the last decade when compared to peers including MSC and Grainger. This permanent dip from 2017 to 2018 at Lawson coincides with the acquisition of Bolt Supply which is a much lower gross margin business than Lawson core VMI business.

While management hasn’t explicitly stated it, I suspect Lawson’s customer base tends to be small repair shops with fewer employees who appreciate the service aspect because of their low staff which would imply they have pricing power. In working with the customer on part selection, Lawson becomes more than just a vendor, but more like a partner. Customers place significant value on the time savings Lawson provides and on not having to worry about managing this inventory. Below is an assortment of customer quotes from various VIC write-ups (Link) and expert call transcripts.

Lawson saves me a lot of time. (My salesperson) knows what I use, and he’s been doing this with me for so long that I just don’t have to worry about it. I’m a one-man show here; I don’t have any parts people. I’m the department, so that’s really valuable to me.”

“Prior to Lawson, we were spending hundreds of dollars a month on rush delivery and maybe 20 or so man-hours a week sending someone to pick-up parts. My Lawson Rep takes a lot of work off my shoulders...”

“Lawson…provides reliable management of our free access items that are critical to our operations…Knowing that Lawson is managing these products, we can focus on our maintenance services and other critical inventory items."

Exhibit I demonstrates that quantitatively, the relationship driven nature of the business shown in sales rep tenure driving rep productivity. There is a very clear correlation between rep tenure and revenue which indicates that better relationships drive spending.

These characteristics create a sticky customer base that values its ability to outsource the management of these parts which leads to 90%+ revenue retention and 50%+ gross margins which stands out among peers. Intuitively this makes sense, the service model lowers churn and customers therefore concentrate spend with DSGR. If you have a sales rep visiting your shop multiple times a week you might as well get everything on the shopping list from them while they are here. This leads to high volume and inventory turnover which drive down expenses and reinforce pricing power.

"About 90% revenue retention and accelerating so we are very, very sticky. Once we have a customer, we tend not to lose that customer." - Lawson Management

"We don't charge our customers separately for the services, it's built into the price of the product, but clearly, there's a value that they are willing to pay high 50%, low 60% from an overall margin standpoint."

Sales reps are said to typically approach breakeven levels in the 12 – 18 month time horizons and approach the corporate average around 2-3 years. Like I said above, The key driver of upside is the improvement of the productivity of the Lawson/Gexpro salesforce as measured by Sales per Rep per Day. New reps are much less productive (year 1 rep $300 per day as opposed to a rep in year 5 who does almost ~$1,600 per day) because it takes time for them to build out their routes.

Lawson also has an unusually high mix of private labels (60% of mix at a higher gross margin than third-party sourced products) which is higher and I have to believe this is a function of being a VMI business (anecdotally I have heard that given a long enough relationship, customers outsource the function of selecting which brand of product to buy). Private label products are generally less expensive than distributing brand name products and as a result, tend to have better operating margins. Suppliers might lose some of their branded product share to selling to DSGR , but 1) if they don’t take on DSGR as a customer, someone else will, and 2) given DSGR emerging scale, manufacturing a DSGR branded product can result in a net-volume uplift, helping with revenue growth, but also asset utilization and typical scale economies.

By my estimate, DSGR sells ~400,000 products while competitors with broader ecommerce presence offer millions. By having fewer SKUs, but more volume per SKU, DSGR ends up with significant pricing power over suppliers. The suppliers that manufacture these parts are pretty fragmented, so I suspect DSGR is typically in the top three largest buyers of parts from any given manufacturer that they purchase from. The service focus incentives customers to purchase more, high volume gives DSGR pricing power over suppliers and therefore DSGR’s share of wallet increases.

The supplier base (DSGR sources from over 6,000) also appears fragmented enough that even if the largest purchasers continue consolidating the industry through acquisitions, it would still be very fragmented for decades. If that’s true, then DSGR is likely to continue to source products at lower cost than mom and pop players for the foreseeable future.

I don’t think all is lost for the supplier. They get a nice volume uplift (especially with the newly integrated DSGR which does much more volume than Lawson did on its own) which makes DSGR an important partner who also benefits from lower prices, and is why I think it is fair to assume DSGR will have increasing pricing power in the future.

I think it is clear that large distributors have a competitive edge over the long tail of small, local distributors, so the next question becomes how do they compare to other large competitors in the space?

There are two ways to really drive a high return on capital. It's either to have wide margins or to have high capital turnover. Industrial distributors were prime targets that faced the Amazon risk in the early to mid 2010s. Amazon acquired smallparts.com in 2005 and rebranded it to Amazon Supply in 2012. Amazon started by offering 500k SKUs across 14 categories within MRO and relaunched this effort in 2015 as Amazon Business. Their entrance into the space altered competitive dynamics although the impact appears to be more in generic, commodity categories. Today, Amazon has more than 500k customers that shop on Amazon Business and its prices are lower than many of the large distributors. Online marketplaces solve two of the primary constraints in brick in mortar. They can have greater breadth/depth of SKU and can offer lower prices.

Grainger (GWW) and MSC Industrial (MSM) decided that they would compete with Amazon on price and selection. GWW increased its SKU count by launching Zoro, an online store for those customers that want a similar experience to Amazon Business. MSM highlights in their investor presentations that customers range from individual machine shops, to Fortune 100 manufacturing companies to government agencies and that they offer 1,000,000+ SKUs through their website, as well as through its +4,500-page master catalog, known throughout the MRO industry as “The Big Book.” They are directly trying to compete with the everything store in a scale game. As a result, both GWW and MSM have seen margins compress and inventory turns increase over the last decade (Exhibit J).

More recently, those brave few who accepted Amazon’s knife fight have begun to focus more narrowly on carving out specific verticals or sub categories within MRO as they realized Amazon may have actually brought a tank. In an attempt to gain market share and preserve differentiation, large distributors focus on a specific niche: Fastenal with fasteners, MSC Industrial with metalworking and DSGR with VMI. Exhibit K shows the decline in Fastenal’s gross margins corresponding with the growth in national accounts which implies that larger customers have greater negotiating power.

While MSM and GWW have accepted lower margins but higher turnover of parts in order to preserve ROIC. FAST and DSGR on the other hand have opted for margins over turnover. This specialty distribution is almost inverse to that general retail model of stack it high, sell it cheap, sell it frequently. They can have high inventory because there is low obsolescence in fasteners, screws, washers etc. DSGR turns its inventory 2.8x per year implying the average part sits on DSGR’s shelf for ~4 months. As my friend YoungHamilton at Analyzing Good Businesses demonstrated in his Fastenal write up, “Goldman estimated that Fastenal products have a 60% premium to the prices found on Amazon, while W.W. Grainger’s online platform, Zoro, only has a 9% premium. W.W. Grainger cut prices the most in 2018, while Fastenal was able to raise prices in FY18 by 0.7%-0.8% and in FY19 by 0.9%-1%.”

I think it is natural for Amazon to continue to eat away at low-cost, low-expertise, low touch item margins. Despite offering more than millions of SKUs, Amazon can keep costs low, and consequently prices, due to scale and very comprehensive shipping and fulfillment network. That said, their high SKU count will make it structurally difficult for them to compete with DSGR on level service. DSGR continues to outgrow the market (4% volume growth last year) because they have focused less on convenience and selection, and more on service. A large chunk of the pats that DSGR sells lends itself well to online sales, specifically the class C parts that accounted for ~40% of revenue post the Hisco acquisition. However, the VMI model continues to benefit both the customer and DSGR. There is more to just delivering the part (see Exhibit G).

DSGR sales reps have deep domain expertise level niches which continue to deliver greater value to customers which allows them to preserve their margin structure and returns on capital. While it is true that a missing bolt that shuts down a job site is extremely expensive, therefore having an item there on time is critical and that these items fall below the corporate cost-cutting radar screen. It is a huge logical jump to assume that price isn’t a factor in the purchase. Price is only mitigated as a factor when it is bundled with a service offering. These small items don’t get price shopped when they are bundled with a service. On their own, however, price matters. DSGR’s VMI focus lowers churn and increases margins which leads to better ROIC than peers.

Lawson’s survival, and the reason behind why the folks at LKCM have called it a gem in the past, can be directly attributed to their VMI offering and their decision to get closer to the end customer. Deliberate or not, Lawson had to embrace a service first model because they didn’t have the scale to compete with large peers and Amazon based on price.

Despite their continued focus on VMI, DSGR has begun to build a competitive ecommerce solution. The company relies on a mix of their existing infrastructure (distribution centers and branches) for first party delivery and third-party shipping/fulfillment.

DSGR will continue to focus on their VMI expertise over the coming years. King mentioned last November that DSGR has, “added 3,300 SKUs in the last 90 days on [their] digital platform.” My expectation is that the company will continue to invest in their ecommerce capabilities and services, but it remains to be seen if ecommerce as a percentage of sales will continue to grow over the next few decades. I suspect orders may be placed online, but sales reps will still deliver to customers daily/weekly.

Most of what I’ve just highlighted differentiates DSGR vs small competitors but doesn’t give DSGR an edge over large players like Fastenal. Any difference in breadth/depth of SKU between the larger competitors is likely immaterial. So, while I think scale does matter at the margin, it’s hard to argue that DSGR has some deep moat. When a small competitor enters into a VMI agreement, DSGR can probably capture some excess return. But when Boeing or Lockheed evaluates manufacturing options, they’re going to get DSGR and their large competitors to all compete on price, and that’s why we have seen MROs compete more heavily on price which has brought down gross margins in recent years. Where scale can still make a big difference is acquisition synergies.

M&A Strategy

Distribution businesses are highly cash generative, much of the investment comes in the form of working capital and capex runs below 1% of sales for most peers. Therefore, the core strategy with the cash the operating businesses throw off is to acquire subscale distribution businesses with a strong service component and improve margins on the back of cost synergies and take customer wallet share. DSGR operating companies have acquired 13 distribution businesses since 2017.

Due to their long operating history in the industry the LKCM team heavily learns on their network to source deals. Management has stated that acquisitions have taken place at 6-8x EBITDA with 7x being the mode, but note that they have historically cheapened those multiple by a few turns through synergies. Exhibit L shows the 13 acquisitions we have data for since 2017 and the EBITDA multiple paid (I assume 8% if not disclosed).

The opportunity to consolidate regional mom & pops is compelling. This is a highly fragmented industry with a runway for M&A and GDP type growth. The fragmentation makes intuitive sense, the industry has tailwinds propelling organic growth in line with GDP (labor constraints, 5G etc) and barriers to entry are low for a small mom & pop with start-up costs. That said, scale can drive meaningful revenue and cost synergies. DSGR is beginning to get to the size where they can take full advantage. For context, there are more than 100,000 mom and pop distribution businesses in North America and I suspect that number is continuously growing because of the dynamics above. I suspect only ~10% fit the description of what DSGR is trying to do with a service focus and size that they can take advantage of scale benefits, but that still leaves a considerable number of potential targets.

Excluding synergies, I estimate that these DSGR can acquire targets for somewhere in the 6-10x EBITDA range. For larger acquirers that benefit from scale, cost-synergies like volume discounts and headcount reduction, combined with modest revenue synergies can drop the implied EBITDA multiple to the 4.0-6.0x range.

Exhibit M shows trailing annual revenue and EV/TTM sales (including Hisco which will close in the coming months) for acquisitions. Acquired targets have had TTM sales ranging from ~$9m - $400b, with the majority less than $50m. The median upfront EV/Sales multiple has been ~0.9x. However, if we assume that the average target had ~8% EBITDA margins, then DSGR’s median EV/EBITDA multiple on acquisitions was closer to 10x, higher than what management has discussed. It is tough for me to imagine that these local businesses are doing more than 8% EBITDA margins considering DSGR as a platform is at 12% EBITDA margins on the back of much greater scale and Lawson was at 7-8% EBITDA margins prior to the combination. If we assume that DSGR successfully expanded EBITDA margins from 8% to 12%, then the median EV/EBITDA multiple post synergies was closer to ~7.5x, which would improve further on the back of cross-selling (to 6x, optimistically).

For larger acquirers that benefit from scale, cost-synergies like volume discounts and headcount reduction, combined with modest revenue synergies from deeper breath of SKU and share of wallet gains can drop the implied EBITDA multiple to the 5.0-6.5x range. At 7x EBITDA, and ignoring all synergies, I estimate that DSGR would generate a low double digit IRR on incremental M&A. However, including all revenue and cost synergies, my guess is that DSGR would generate high teens to low 20% ROIC. This M&A is clearly accretive.

I estimate that a 1.0x EV/Sales multiple is equivalent to a ~11% ROIC at the operating entity level after all cost synergies. In order to earn consistently high returns on the growing M&A budget, DSGR has to keep the average acquisition size small. All else equal, as deal size gets larger, incremental ROIC falls because of less cost synergies and generally higher multiples.

As far as cost synergies go, purchasing power and shared services consolidation is extremely low-hanging fruit and improves EBITDA margins by 1.5%-2% almost immediately as we have seen at Lawson and Gexpro.

Certain buyers of regional distribution businesses (like private equity firms) wouldn’t benefit from these volume discounts. The fact that LKCM had to merge with Lawson to get these businesses to scale speaks to this and therefore feels like a durable edge when competing to acquire subscale targets. Given DSGR’s scale and the stickiness of the underlying services they should be able to push price through as we saw in 2022 when they took 10%+ price at Gexpro and Lawson.

LKCM has plenty of experience managing their integrations well and should be able to increase acquisitions/year while maintaining a low average deal size. I’m not that worried about DSGR actually finding the deals because of their existing relationship and large numbers of potential acquirees.

The other risk to consider is increasing competition in the space, which could impact DSGR in two ways: 1) more M&A competition could decrease M&A IRRs; and 2) industry consolidation could lead to increased pricing pressure on products and services.

We have seen purchase multiples rise to low double digits from the mid single digits we saw pre-COVID. I think with the macro backdrop it is reasonable to expect multiples to come back down. I think this is a longer term risk and worth watching the trend in multiples paid. Despite consolidation efforts, I expect the market to remain extremely fragmented over the next decade as new entrants prop up the number of potential acquisitions and it would be silly to underwrite huge market share gains. I also expect that DSGR will continue to sole-source some of their deals, which should generally result in better prices.

DSGR operates under a decentralized operating model (Lawson, Gexpro and TestEquity retained their brands and individual management teams) with capital allocation centralized through LKCM. As I touched on in my APG piece, scaling a centralized M&A function can be hard which typically leads to larger deals being done to use up the ever growing stream of cash flow. Typically, when deal size increases, IRR falls. These larger deals are more competitive on average. However, because of the massive fragmentation of the market I wouldn’t expect to see deal size rise too much. We haven’t seen multiples come up over the last few years so it suggests there isn’t enough competition to drive prices up. As a result, DSGR would likely fall short of their 1-3% EBITDA margin uplift from better volume discounts.

This management team, because of their PE background, is extremely disciplined and this shows up in their ROIC and ROIIC focus. Bryan King said recently, “I have cringed at the roll up term used in the 90s, if there's not a deliberate reason to make an acquisition where you think it makes financial sense and the long term sustainability at your core better, then there’s not a real reason to go out. The returns on incremental invested capital in working capital are so high in distribution businesses that you can compound your business very attractively through capital invested in working capital or internal initiatives.” I am willing to bet that the reason they are turning towards M&A despite the high ROIICs on working capital investments is to deploy ever increasing amounts of capital as this platform really turns on.

Management

CEO Bryan King founded LKCM Headwater (the PE arm of LKCM a $24b investment firm in Fort Worth, TX) and has almost three decades of hands-on industrial distribution operating experience. King has invested over $60 million of his personal wealth into DSGR and takes 0 compensation from the holding company so his only path to returns here is through the stock working. 1/3 of LKCM Headwater's $2b in capital came from the investment team, affiliates and related parties so they are highly incentivized to make this deal work.

Insider ownership here is pretty crazy. LKCM and its affiliates own 77% of the common stock and King and his family personally own ~20%. Even during the recent Hisco deal, the company did a rights offering to raise capital for the deal which would have been a perfect time for insiders to lower their stake through dilution. Instead, all LKCM affiliates indicated that they intend to fully subscribe to the rights offering and fully exercise their oversubscription rights to maintain (if not increase) their stake. Also if this isn't’ compounder catnip, I don’t know what is. “Our underlying philosophy is anchored in a discipline to allocate capital to the highest return projects while building the best positioned long-term specialty distributor with the deepest and widest moat possible around our value added focus areas of leadership for our customers and shareholder partners.”

Given Bryan’s control, shareholders in DSGR are ultimately making a bet on him and the LKCM team and their ability to manage this business to the benefit of all shareholders for what will likely end up being a decade or more.

The LKCM team has been in the distribution space for decades at this point and their track record is impressive. They were former owners of IDG, Rawson, GSMS and Bearcom and currently own Building Controls & Solutions and Relevant outside of the DSGR entity. Given this experience, I think it is pretty clear that Bryan has built relationships in the industry and has been able to build the management team at the operating subsidiaries to his desire.

Each of the operating subsidiaries have their own CEO and CFO. Lawson’s CEO was brought in during 2022 from an operating company of a PE firm and has previous experience at Grainger. Beyond him the long tenures of each of the operating subsidiaries management’s team is impressive. Lawson's CFO, and both Gexpro CEO and CFO have been in their roles for over a decade. TestEquity’s team is relatively new but has been in place for 3+ years now. Each of these businesses are given their own autonomy.

As a capital allocator I think the M&A track record and Bryan’s PE background speaks for itself. This business is not very capital intensive (capex is 1% of sales) so the majority of investment is through working capital. Distributors will flex their balance sheets to grow and scaled distributors have the added benefit of flexible payment terms for customers. Many of DSGR’s customers get paid after a project is complete, but because DSGR has tens of thousands of customers they can extend payment terms for customers which allows their customers to take on more business.

As revenues increase, working capital follows which means cash conversion from EBITDA in a growing distributor is somewhere below 100%. Management has discussed that they are currently running at an elevated working capital level and that working capital should be ~20% of sales. All of this said, building out the salesforce for VMI and other thigh touch services is a bottleneck and requires incremental spend which weighs down ROIC. Exhibit N shows NWC as a percentage of sales for the peer group. Although the range is wide, DSGR is about average in the peer group..

This also works the other way when revenues are declining cash conversion tends to be greater than 100%. For example, when LKCM bought IDG in August of '08 and were immediately faced with a decline in revenue because of the GFC they ended up “throwing off a lot of cash'' when other companies were tight on spending meaning they could go on the offensive and acquire other businesses just as multiples were getting cheaper. The three important takeaways here are that EBITDA dollars and margins are resilient through even difficult economic conditions, DSGR can delever very quickly if we go into a recession so the balance sheet is in great shape and they could use this strength to actually deploy more capital as lower multiples.

It is also worth noting how much capital DSGR has to deploy to generate those EBITDA dollars. I am working off the 2022 10K which is now a bit dated because of the Hisco acquisition but can still provide directionally helpful answers. The gross value of PP&E is north of $82m, where most of that is investments in buildings and equipment with an average useful life of about ~10 years. As a result, DSGR spends $8m/year in maintenance capex. As mentioned, working capital tends to be ~20% of sales and was $308mn at year end 2022. In all this means that DSGR ROIC is ~28% ($110m UFCF in 2022 . $390m NWC + PPE). This industry tends to have a heavy ROIC focus where scale distributors don’t engage in a constant knife fight as the market is large and stably growing so they don’t have to compete head on or hurt each other's ROICs. As a result I believe DSGR’s strong returns on capital and incremental capital will continue to persist for a long, long time.

Returns on capital can be astronomical but it doesn’t matter if you can’t put any capital to work. Intrinsic value growth is a function of returns on invested capital and the reinvestment rate. If management commentary holds and working capital remains at ~20% of sales and capex at ~1% DSGR will be able to reinvest 20-25% of NOPAT. At a mid teens ROIC (13-17%) this means DSGR can grow intrinsic value ~5% per year organically. On top of this management is likely to find accretive (but lumpy) M&A at mid to high teens ROIC with the rest of FCF which means DSGR can grow intrinsic value 14-16%/year.

Management and director compensation is tied to adj. EBITDA (60%), Net Sales (30%) and Net Sales from Acquisitions (10%) which prioritizes growth and margins at the operating level. I would normally be concerned that compensation based on net sales from acquisitions would incentivize M&A at any price and breed a lack of discipline in capital allocation, but the roles of operator and capital allocator are separated at DSGR. Admittedly, I would prefer if management compensation was actually tied to a combination of metrics at the operating level as opposed to corporate wide metrics. Why should execs at Gexpro get paid if TestEquity outperforms? Long-term equity incentives are a mix of RSUs (20%), PAs (40%) and MSUs (40%). The options vest in equal increments over four years, with a seven year expiry.

In my view, DSGR shareholders are partnering with a rare combination of great capital allocation and operational ability. These folks are thoughtfully evaluating every lever that can be pulled to generate value for all shareholders.

Balance Sheet

Characteristically, DSGR has a heavy debt load due to their PE management. Management will often take leverage up to take on an acquisition (as we have seen with Hisco) but has stated they target a 3-4x net debt/EBITDA leverage range. The absolute dollars of debt has remained consistent and deleveraging has happened at the business through EBITDA growth.

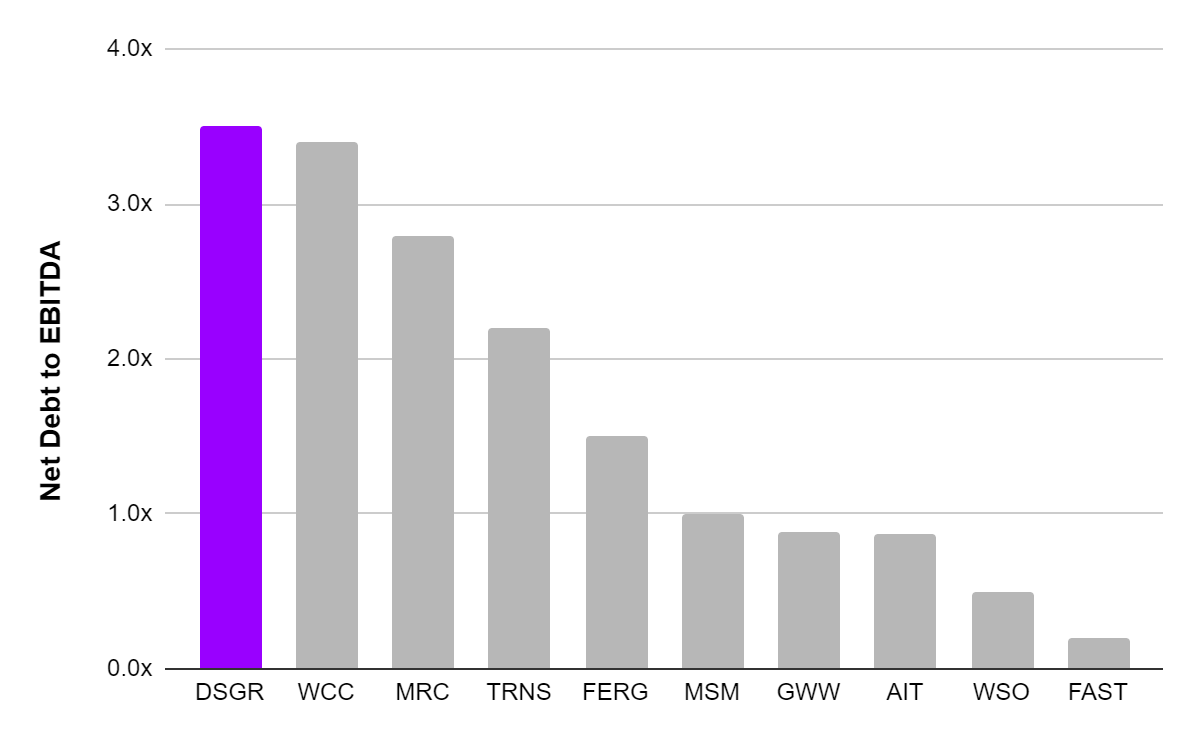

Despite the rapid EBITDA growth, DSGR still has proportionally more debt than any of the other distribution businesses in the comp group (Exhibit O). As a result of the earnings power growth and starting leverage, it is unlikely that they will have to use FCF to pay down debt over the next 5 years to get into the 3-4x range.

Regardless of the metric used, DSGR is trading at a discount to the comp group (after you account for the wonkiness of how GAAP treats M&A), and I suspect one of the primary reasons is a higher-than-comp-average leverage problem. I think it’s been established that DSGR’s margin structure is flexible should revenue decline and that conversion would likely increase in that event, but it is reasonable for investors to want to see it at such a newly public company before they believe it.

The bigger problem seems to be that the weighted average interest rate that DSGR is paying today could increase if rates continue to rise which would reduce FCFE. In Q1, DSGR was paying 7.1% on their outstanding debt balance which is floating and due in 2027. As a result of the Hisco acquisition they are going to have to take on ~$170m more debt which will bring leverage to 3.25x-3.5.

Valuation

Lawson had historically grown 3-6% per year through a mix of both volume and price and we don’t have enough data on TestEquity or Gexpro to draw any conclusive assumptions. In its short life as a public company we have seen volume growth of 4% with pricing of inflation plus 2-3% which indicates the business can consistently grow mid single digits. I have DSGR growing topline 6.6%/year through the forecast period see Exhibit P. There are a few reasons why I have organic growth above the historic base rate. I believe that DSGR can grab a higher share of wallet among customers because of an expanded range of services offered through cross selling and growing SKU count will incline customers to concentrate wallet share with DSGR and reduce lost sales. DSGR will be able to better service large national accounts because of their broader geographic scale and finally a positive industry outlook driven by onshoring and higher mix of faster growing T&M sales post Hisco acquisition.

Margins

Lawson has the highest gross margins by over 20% and the mix shift between the three segments will determine how gross margins progress over time. As a rule of thumb TestEquity has the lowest gross margins and to the extent it is the fastest growing segment will be a headwind to gross margin % going forward but drives gross margin dollars. Over the forecast period I have gross margin growing modestly from 33% to 33.6% driven by an incremental gross margin of nearly 36%. Margins gains are driven by volume discounts with suppliers through greater purchasing power offset by mix shift to TestEquity. Distribution businesses in general don’t have issues passing on inflationary costs increases to end customers and I presume because of the higher touch model that DSGR employs they can take excess price on top of that which helps preserve margins. SG&A as a % of revenue, mostly labor and tied to headcount, had been in the mid to high 20% range for Lawson and Gexpro/TestEquity pre merger and we have already seen this number drop as a % of revenue through integration and scale economies. As a result I have SG&A falling from ~26% today to 22.5% in 2028. In all I have EBIT margins going from 7% to 11.1% as DSGR benefits from scale economies and Hisco benefits the overall margin structure of the faster growing TestEquity segment. Exhibit Q shows my go-forward EBITDA margins and EBITDA.

In Sum

The DCF model shows that fair value in my base case is ~$72.00/share, which is 59% higher than the current share price. A snapshot of the model is shown below. Another way to think about this is that looking out to 2027 an investor could expect a 27% annual return in the base case.

The risk return potential of DSGR is very skewed. Even if revenues were to grow 3% annually (implying no market share growth), EBITDA margins were to only get to 13% and DSGR traded at 10x EBITDA on 3.5x net debt to EBITDA I get a share price of ~$47, in line with today’s price.

Sources:

5/17/21 13D

12/29/21 Press Release

12/29/21 Presentation

1/14/22 Preliminary Proxy

MSM Investor Presentation Q2 2023

March 31 Hisco Acquisition

November 2022

MCJ Capital Partners Q1 Letter