To start, this is written by someone in their early twenties who has never worked in a software business before and lacks first hand experience, many of these ideas purely from what I have read such as the wonderful resources at Tidemark. I am deeply interested in the space and would love to receive any feedback and learn about practitioners' real world experiences. If you would like to get in contact please reach out. I want to learn from you.

Jim Barksdale, the former CEO of Netscape, once famously proclaimed during Netscape’s roadshow there are “only two ways to make money in business: one is to bundle; the other is unbundle.” I believe that now is the time for bundling in vertical market software. The successful VMS companies going forward are going to be platforms, not point solutions. As software has had quite the heyday over the past ~15 years, and investors have fallen in love with the business model it has attracted a lot of investment capital and new entrants. Inevitably this has led to decreasing returns on capital and increasing capital intensity making life tough for the average software business.

The frameworks and ideas in this essay are guides to help separate the best of breed vertical-defining businesses that have the potential to be “industry evangelists” from the vanilla software. I believe that vertical market software has the potential to be a rich pond to fish in for investors and operators looking for exceptionally high quality, durable businesses. As the trusted software vendor to your vertical, you have the right to win against generic third-party providers by delivering a vertical-specific offering that is often more usable, more affordable, and better integrated with your software. Vertical markets are smaller and can be better defended and allow you to develop a maniacal customer focus. There are typically a few sources of competitive advantage in application software:

Mission-critical system of record, e.g., payroll

Great product with strong organic demand and efficient GTM, e.g., Atlassian

Becoming an industry standard and how a swath of people do their job, e.g., Salesforce

Strong ecosystem dynamics, e.g., Bill.com

Discover an underserved segment or market early and quickly, e.g., Veeva

Vertical software has the potential to capitalize on all 5. Why is this happening now? 1) There has been a decades-long build shifting us from object-oriented computing, to service-oriented structures, to today’s composable/headless architectures. This underpinning allows application components to work better together and build off of each other. 2) The consumerization of IT has made UIs and workflows far more intuitive and native. 3) Whenever an existing software can’t do what you want, no/low code technologies can now help fill the workflow gaps.

The end customer defines many of the challenges and opportunities of VMS. As the VMS vendor you are the industry arms dealer. Most verticals are highly fragmented, and the end customers are typically small business merchants. The software buyer for these merchants is often the owner, or sits next to the owner, and is a significant user of the software. This is an important and positive dynamic in Vertical SaaS: because the software buyer is also the user, they are familiar with the products and value proposition, and have singular decision authority. There is no better customer to have than the one who writes the checks for the organization. This also means you have to be one platform. These owners are busy people often wearing every hat in the organization. IF anything goes wrong, they want vendors to go to.

This essay’s purpose is to codify frameworks used to identify these truly exceptional companies. When the full potential of VMS is realized they can be some of the best businesses in the world and I believe running one is similar to what John Malone described in running TCI in Cable Cowboy, “'When you've got it running right, when you've got it structured properly, it's like flying the most powerful fighter jet in the world.”

Tidemark has created the wonderful Vertical SaaS Knowledge Project and developed the Win, Expand, Extend framework. Within this framework the goal is to 1) Win the Category by occupying the control point or owning the critical system of your target customer 2) Expand by cross selling new products and 3) Extend through the value chain to other stakeholders

VMS is opinionated. It is designed to embed the customs, assumptions, and best practices of a specific industry into the product. For example, tipping is common in service industries, percentage of completion payment is the standard in construction. Some industries operate on a cost-plus model, while others are more time-and-materials. The best VMS vendors understand and support these nuances across their various products.

Going after a “smaller market” is the point. Fewer competitors are being funded to compete and winner-take-most advantages prevail. Being affiliated with the vertical is the goal. Vendors become known for an end market. “If you’re a GC, you should really pick Procore. They’ve been built for GCs.”) This focus also extends to the workforce—by staffing the entire org with employees who truly get the vertical you are serving (typically by hiring from within the industry) everyone from product to sales speaks your customer’s language. This relentless focus on the end user is a pretty Bezosian belief. Most vertical markets are local, and local merchants talk. Once a vendor reaches a certain threshold in local market share it becomes easier to grow because word spreads. There may also be some marginal network effects as owners and employees become familiar with your system. When they switch jobs or start a new business they will bring along the tools that are familiar.

On the flip side: you have a limited lead pool. Because of the finite end market, you should avoid creating a sales culture that just burns leads. In addition, local market brand awareness and light network effects warrant investing in relationships. That doesn't work if every merchant gets a call every day—you have to build rapport.

Control Points

SMB operators crave a single point of accountability (you’ll often hear the desire for “one throat to choke”), leading to the consolidation of technology stacks into one or two core systems. The value for the merchant is pretty clear - a unified and straightforward platform to run the business and incentives are tightly aligned between the merchant and vertical SaaS provider (VMS providers often become industry cheerleaders/evangelists). The number of SaaS apps used per department in large enterprises often exceeds 60+ point solutions. This is entirely too many.

SMBs oftentimes rely on a patchwork of horizontal software products (think Mailchimp, Typeform, Google Suite, etc). But just as it does with larger companies, this patchwork leads to fragmented data, and fragmented understanding, across business functions. Where’s the source of truth for the list of ‘active customers’? Where’s the single, true, complete list of all products, services, delivery dates? Tools like Zapier and Paragon help with data portability, but don't provide that single source of truth. These businesses are still stuck juggling multiple logins, monthly subscriptions, and duplicate data.

The control point is the last tool to be shut down before an owner ceases operations. From this position, because of the gravity your system commands, you have the unfair right to cross sell other products out of the control point and go multiproduct. For this reason, if you are not at a control point everything should be subsumed by the goal of building or buying a product that gets you there or renders the existing one a “dumb database in the back closet.”

There are typically one or two control points (sometimes you’ll hear these called “systems of record” or “operating systems”). One of these is in the front office and is generally a POS or CRM. This front office control point gathers and holds the customers most important data. The front office control point helps generate revenue and brings in customers. The other control point is in the back office. This can be the company’s ERP or general ledger. The control point holds the company’s most important internal data and allows them to run their day to day operations. This is why it is usually one or two VMS players that dominate any given market.

Control points can also exist in employee management (systems that facilitate payroll, scheduling and communication) and Fintech (systems that allow for the capturing of payments and transactional data and bring in funds. Tidemark found that Front Office at 37% and Back Office at 20% are the most common initial control point categories.

Control Points can typically be identified because they hold some combination of the three types of gravity 1) Workflow gravity 2) Data gravity 3) Account gravity. As Tidemark has articulated,

Workflow gravity is where the most users spend the most time. It’s the system other systems integrate into. Not all workflows deliver the same value. If you are the place where people create, you have an advantage of cross selling down the stream. This is how Autodesk is attacking Procore and why the Bloomberg Terminal was so powerful for Bloomberg’s expansion into financial institutions. The more time you are in front of someone, if you are the first system they log on to in the morning and the last they log off of at night the greater chance you have to sell them more solutions and the less likely they are to churn.

Data gravity is when the system creates and holds the most critical information that is scary to migrate. No one wants to risk changing the software with the most important data for fear of losing it or other terrifying second derivative impacts and delays so churn is exceptionally low. This data is typically financial or identity data. It is critical to a client for understanding their customers (e.g., CRM) or managing risk (e.g., compliance). CRM or ERP implementations can take years in many instances and de-rail entire companies.

It is also worth considering the lifespan of the data being collected and how incrementally useful it is. CRM data may have a much longer relevance to the organization and each new SFID is relevant. Account gravity occurs when the system user is the highest-ranking individual in the customer organization. Tidemark writes, “If your biggest advocate and user is the one signing the checks, you are sitting pretty.” This relationship is a two-way street. When you vendor to a customer’s most powerful employee, you also have an unfair right to sell them another product because they trust you and you have their attention.

Once you occupy the control point and have reasonable GTM unit economics, you want to default to quickly scaling locations served. If you have properly identified the control point, you will have the opportunity to sell other products later down the road. The lever of increasing ARPU through product penetration should only be pulled once location growth begins to decelerate. The goal is to saturate the control point’s TAM before launching any expansion products.

Understanding Unit Economics and Why Point Solutions Fall Short

Tren Griffin refers to the five variables of the LTV formula as the five horsemen. Lifetime value, the net present value of the profit stream of a customer is determined by the: 1) ARPU 2) Average Customer Lifetime Value 3) Cost of capital 4) Costs to support the user in a given period 5) CAC. What he envisions is that a rope connects them all, and they are all facing different directions. When one horse pulls one way, it makes it more difficult for the other horse to go its direction. Tren’s view is that the variables of the LTV formula are interdependent, not independent. If you try to raise ARPU (price) you will naturally increase churn. If you try to grow faster by spending more on marketing, your CAC will rise. Churn may rise also, as a more aggressive program will likely capture customers of a lower quality. As another example, if you beef up customer service to improve churn, you directly impact future costs, and therefore deteriorate the future cash flows.

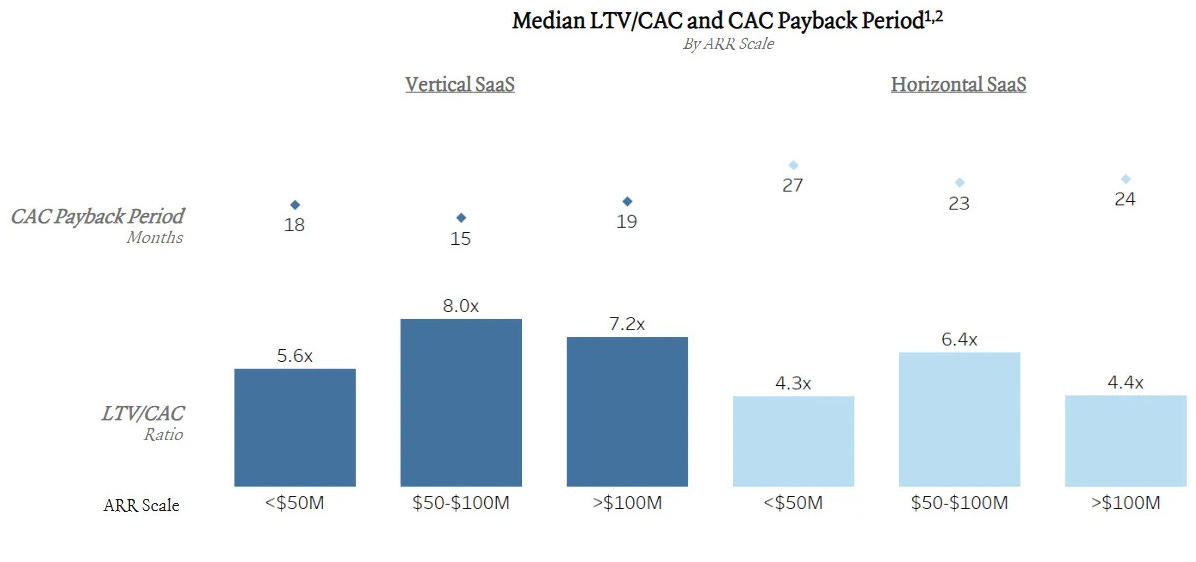

For most SaaS companies, the upfront cost to acquire a customer is greater than the first year of gained gross margin, meaning the paybacks take longer than a year and most profits are created over time through high retention rates and thus high lifetime value (LTV). Adopting a multi-product approach where a company cross-sells more products to current customers should in theory improve unit economics by adding more gross profit with meaningfully less acquisition costs. By expanding in the customer, your VMS is commanding more and more gravity which reduces churn. The implication on unit economics is that the company with a lower churn rate will structurally have higher long-term margins, and therefore, the value of their revenue stream and installed base is higher because they have higher and more durable free cash flows which leads to higher valuation. Take, for example, the below. This first scenario is a single product VMS vendor that has $6,000 average revenue per account annually. Industry surveys suggest these companies have ~88% annual retention or 1% monthly churn. On the other hand, scenario 2 is a multi product VMS company that has $10,000 ARPA annually and reduces churn to 0.75% monthly (91% annual retention). The result is that the mutli product company can spend up to 33% more to acquire a customer and still wring out the same economics as their point solution counterpart.

This incremental ARPA driven by expansion products is not unreasonable. Surveys have found that CRM products drive an incremental $6,000 in ARPA while quoting, scheduling and communications products can drive incremental ARPAs of $3,500+.

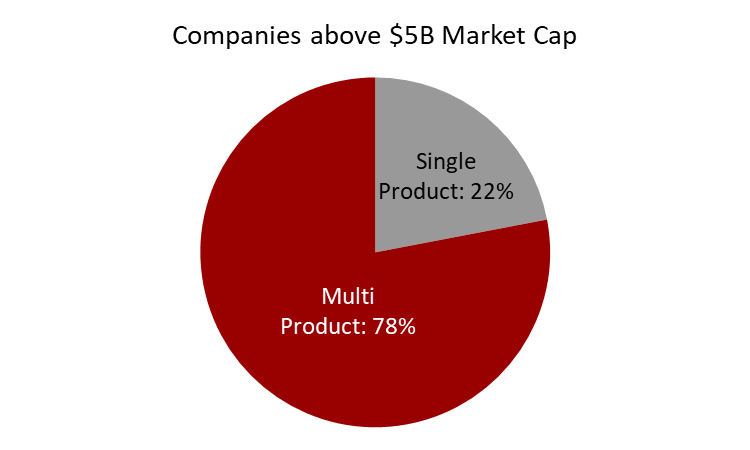

Older cohorts also can become incredibly profitable as you sell the installed base more products and increase ARPU. Once net churn goes below 0 (e.g. net revenue retention is about 100%) it is similar to having a retail store that is growing sales years after it is built (this is why SSS is so closely tracked in retail concepts). That incremental margin can be invested in R&D for new products to enhance this flywheel. This is borne out in industry surveys of VMS vendors backed by growth equity funds that note single product companies have net revenue retention of 108% on average while multi-product VMS vendors have NRR of 111% Put simply, you have more ways to win by being a multi-product company with Act II, III, IV, and beyond.

The result is that point solutions are stuck in the middle. There are too many benefits of using a VMS platform that customers would prefer to choose one of those vendors versus using 100s of point solutions. Point solution software was great when building software was hard and there wasn’t much competition. But that is not the current environment, the cost of capital in software has fallen and the barriers to development are ever plummeting. Building differentiated products is nearly impossible in 2025 with point solutions since you have limited ability to be different from the 100s of others out there which leads to pricing disadvantages. Being in a niche or multi-product gives you more pricing power. Those with multiple products can absorb pricing pressure a lot better and keep higher gross margins. As Akash Bajawa points out, “point solution excellence eventually evolves into multi-product greatness or secular decline (approximately ⅓ of the public single-product companies as of the end of 2016 were acquired by the end of 2022).

Software companies that are single-product have been powered by the twin tailwinds of cloud transition and low-interest rates over the last decade so as those tailwinds have abated the inherent weakness in the model is becoming painfully and rapidly apparent. Multiples are being crushed, and companies are struggling to grow as they once did.

A company typically starts to scale with its best customers. The product market fit is so strong that a customer will trust its business to a small, raggedy startup. Selling into this ideal customer is, well, ideal. They are acquired and retained cheaply because the product solves such a painful problem for them. As a company seeks to scale, it often needs to sell outside of its ICP. There’s a learning curve and lots of execution that goes along with this expansion—but when a company finally achieves this Herculean task, they will discover, to their horror, ever-diminishing returns to scale in sales and marketing spend. The further they expand, the less ROIC each customer will bring and unit economics begin to erode. As they keep growing, they find that they need to drift further and further and further away from their ICP and see diminishing returns to scale. These single-point solution companies, hooked to a never-ending sales and marketing dollars treadmill, are doomed. These businesses are linear: to grow, a company must stuff in as many salespeople and marketing dollars as possible. In Salesforce’s language they are Campers. They have constant dollar additions in ARR which leads to growth decelerating to zero low growth sustainability.

The goal, of course, is to be a “Trailblazer” that maintains a constant growth rate net of attrition.

Not all Control Points are Made the Same

Different control points exhibit different retention profiles and java different attach rates for secondary products. Fintech and Back Office control points exhibit the highest Gross Revenue Retention while Respondents with Fintech and Employee Management control points exhibit the highest Net Revenue Retention.

Means of Ascent: Going Multi-Product

Once you have earned that unfair expansion right, you can start to leverage gravity in your favor. The best vertical software companies build a latticework of new products that drive continuous growth. In turn this expands their TAM and allows them to spend more to acquire customers and drive further down market with their new ability to capture a larger portion of customer spend. This unlocks new customer segments that were previously uneconomic to go after. The beautiful part is that selling multiple products to the same customer can deepen the customer relationship, increasing NRR and driving lifetime value.

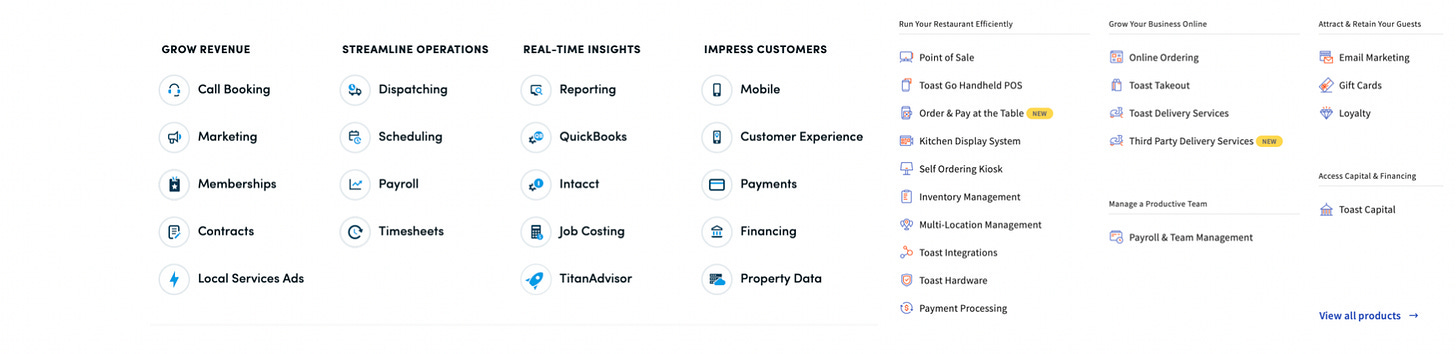

Look at ServiceTitan or Toast:

How do you know when it’s time? Well, you start hitting the ceiling of the location count in your geography, and growth slows. As you saturate your segment, you will start to see increases in customer acquisition costs (CAC) and close times.

However, the sequencing of multi-product is important. The ultimate goals is to own the category, which means you must own the control points. If you have the resources, focus on locking down any potential competing control points first. Once you occupy the control point it is more science than art, influenced by the data that’s being collected by the wedge and how it confers an unfair advantage to build the next module. As Tina Dimitrova said at Bain Capital Ventures, “It’s a more logical product strategy to go from expense management –> A/P automation –> procurement –> forecasting –> working capital loans, or a similar path that builds on the data a CFO tool has already acquired.”

Willy-nilly rolling out a dozen different point solutions that don’t integrate or don’t connect well together isn't going to meaningfully improve the value you deliver to customers and therefore your unit economics are unlikely to improve. The truly special platforms are thoughtful on how they sequence which product they roll out.

Look for products that have deepen your gravity. An additional product should add to your data, workflow, or account ownership, and compound on your control. Ask yourself “how do we make our project one that people are going to check everyday?”

A more thoughtful approach is to follow where your users workflow and data gravity lead to and analyze customers’ spend pools are. Each new product should make your existing products better. Tidemark has laid out this idea with their “Follow the Workflow” and “Follow the Money” patterns of expansion. I like to frame it that actions express priorities. If you want to know what people care about don’t listen to what they say, look at their calendar and their budget. How people spend their time and money tells you what they actually value.

Look at their calendar (LATC) focuses on expanding a product suite by moving into the next step in a customer's operational process. Think of it as moving along the customer’s day-to-day workflow, one step at a time. Merchants ideally want a single vendor, so it’s natural to add functionality onto the ends of your current workflow. In vertical markets (like healthcare, construction, or education), workflows tend to be well-defined and repeatable. If a software company starts by solving a key part of that workflow—say, scheduling appointments—it can expand by offering products that help with what happens before or after that task, like intake forms or billing. LATC starts by automating the most important processes, then following those to the interlinked processes and people. By connecting processes digitally, you make them better together: you add efficiency by increasing speed and reducing errors/manual labor with digital handoffs. In a perfect world, data from one process can help automate the next. Even better, your customers will generally lead you to a product and how to sell it to them. Just follow their needs. The beauty of this approach is that you’re not asking customers to reach into their pockets and buy more software. Instead, you’re replacing something that customers are already paying for which makes the cross-sell feel “free” and lowers sales friction.

Look at their Budget (LATB): As money flows across multiple activities or functions within an organization, a software provider follows the money to build a product for each step in the process. LATB also makes it natural to extend across multiple stakeholders (in every transaction, there’s a buyer and seller). To avoid reconciliation, payment delays, and other errors, there is a strong impetus to have buyers and sellers automate through the same set of software and payment rails. The end goal is to have an efficient, straight-through processing across multiple firms. In LATC, it's about increasing the speed of business; in LATB, it is about removing delays. For example, if your initial product helps dentist offices manage patient bookings, you might expand into billing or procurement. Help customers with something that ties directly to revenue or cost savings. Specifically target pools of your customer’s spend. Get a glimpse of the P&L and ask yourself what you can go after.

Further, each potential expansion product should be measured by the impact it has on you, your customer, and the customer’s customer. Vertical markets tend to be small places where word travels fast. You can't slash and burn. As a starting point, the new offering should be evaluated on:

ARR impact

Gross margin impact

Customer adoption impact

Retention impact

Level of effort to build and launch the solution

Ability to obtain high customer adoption of the solution

The pros for you and your customer are clear:

For the Vertical SaaS Vendor (VSV):

Creates new revenue streams with high gross margins. You can increase overall gross margins for the entire company while having dramatically lower acquisition costs per product.

Allows for diversification on top-line growth. Not all products have to hit annual goals over time; it’s a portfolio approach that allows for a more nuanced growth strategy.

Enables higher stickiness for existing customers on the core software by increasing net dollar retention.

Attracts prospects due to the additional features and functionality that can differentiate you from competitors.

For the merchant:

A better experience for the end customers (e.g., they can do payments in the same UI)

A better experience for their own staff by reducing the need to learn multiple systems

Ability to generate additional revenue via marketing automation

Ability to increase efficiency through things like embedded payroll and reduced errors from manual calculations

Extending throughout your customer means that instead of a single team making the switching decision, they now need to get buy-in from multiple departments. Good luck. This is how Epic has managed to stay so deeply entrenched in hospitals and never lost a customer in their 40 year history.

The end goal of multi product expansion is to become the single source of truth: you want customers to always ask, “Did you check [YOUR PRODUCT HERE]?” Eventually you want to centralize all of a customer’s critical parts, its inputs, its outputs, and all the processes in between. When you are the single source of crucial data, everything goes through you. You have an unfair right to build other apps (particularly analytical apps) that leverage this data and serve other functions or constituents. Salesforce is the absolute best in the world at this.

Common Products and the Lending Opportunity

Embedded payments can create a seamless purchase experience for customers and dramatic optionality for Vertical SaaS Vendors (VSVs). It allows VSVs to uniquely position themselves as a point of trust, a point of depth, and ultimately, a point of data. Appfolio has already gone and done this.

Payments provide key data and money movement workflows, which can be leveraged into adjacent financial services like lending, instant deposit, issuance, and fraud.

Lending is a great example of this. Software companies like Shopify are starting to source and underwrite business loans. Vertical software providers that have visibility into cash flows are particularly well-positioned to originate and underwrite loans. For example, Procore is delivering loans to help construction companies finance the purchase of construction materials at the moment when a new job is awarded to them. Mindbody is offering cash advances against future payments processed through the Mindbody platform. When conducted alongside payments, it provides extremely low CAC as the VMS vendor leverages the financial trust and connectivity built through software and payment experiences (as well as expedited applications from prior payment onboarding). If you are processing revenues via your payments offering and have access to more data about a vertical than any other company, then providing capital to the space becomes a logical next step. As a customer, banking with your VMS provider is the most convenient option and in many verticals the only place where capital will consistently flow.

The customer benefits from easier access and lower ongoing operating costs as payments data streams drive superior underwriting for the vendor. Collections can also occur seamlessly through the payments flow (auto repay as customers spend at your client), improving collection rates and reducing the servicing burden on the merchant. These services benefit you and the merchants, adding to the loyalty ecosystem and creating a flywheel effect. The VMS business gets healthier as the underlying customers get healthier and their market grows. This ecosystem creates rich sources of data and higher dollar volume processing, which you then get to monetize or reinvest into your customers.

Becoming an Industry Evangelist

The final evolution for a best in class VMS business to become the connective tissue that glues the industry together. Once you have occupied the control point and expanded into multi-product the next logical step is to extend up or down the value chain and begin to work with your customer’s customer or suppliers.

If your business is levered to an industry, you want that industry to grow. VMS vendors are in position to make this happen. Again, you are the arms dealer to your industry. You can help generate incremental demand by increasing customer access through financing options (BNPL), conversion through customer confidence (certification, fraud, etc.), integration into more demand sources (e.g., channel management), or improvement of the repeat rate through a CRM and loyalty programs. On the cost side, because you have aggregated the buying power or attention of hundreds or thousands of SMB you can begin to source supplies for them as Slice as done by placing bulk orders for pizza boxes and other supplies for the pizzerias it serves.

In an industry where the merchants are small businesses and their suppliers are much larger, a group purchasing organization (GPO) can be an effective and natural multiplayer offering, leveraging collective buying power to buy at lower prices and better terms. If executed well, a VSV’s GPO can drive serious volume for suppliers and remove the cost of selling and negotiating with thousands of merchants individually.

If your industry is restaurants or HVAC or construction or mechanics the biggest potential headwind to industry growth over the next 30 years is a lack of qualified labor. So, training and accreditation become logical expansion points eventually.

When you offer credit, insurance, or improved working capital management, it can help your customers grow more quickly. Once you have done this, you are on your way to becoming what I call an Industry Evangelist. In effect, you become the industry standard and an ecosystem begins to form around you. You can create a single source of truth upon which you can build multi-party applications and solve industry-level problems.

As the size of the customer base grows, some vertical SaaS companies will also become marketplaces. Shopify is in the vanguard here, and is building toward marketplaces on both the supply side (developer and expert marketplaces) and the demand side (Shop app). Mindbody has a customer facing app for discovery and booking. Toast is increasingly competing with Doordash and Uber Eats. Vertical SaaS can be somewhat disruptive to marketplaces because they start with onboarded supply and margin built in from payments volume. Toast, as an example here, charges a fat flee per delivery vs the take rate model employed by marketplace pure plays.

Data Business Optionality

Data remains one of the most under-exploited opportunities in vertical software. Many of the most valuable vertical technologies have standards based moats. Companies like FICO, Verisk, Refinitiv, MSCI, SPGI, and MCO are data businesses at their core. They have grown to billions in revenue with extremely attractive margins, recurring revenue, barriers to entry and trade at 30x+ earnings. To date, few application software companies have built data businesses. But we think this is one of the under-served opportunities to grow revenue and build deeper moats. The data you collect can be used for benchmarking and industry analytics. Guidewire allows users to see anonymized operational metrics benchmarked across similar Guidewire customers.

A variant of benchmarking is compliance and credentialing. In some industries, a VMS vendor can get large and credible enough to become a true industry standard. In such a case, the cross-side network effects are powerful. Merchants seek, and can rely on, the ratings you have collected on suppliers, and suppliers can market themselves to new merchants using your rating. These standards can become embedded in an industry and make supplier search or merchant credit worthiness much easier to evaluate.

Conclusion

Tidemark has argued VMS vendors' progression should be Win the Control Point→Expand Offerings→Extend through Value Chain. The goal should be to win the control point of a single company by becoming the steward of the most important data or process of a business. Next, expand offerings such as payments, payroll, and insurance to increase LTV. From there, you extend through the value chain to other stakeholders: suppliers, employees, and consumers to increase TAM.

The last twenty years of digital proliferation and cloud have allowed a field of a thousand point-solutions to flourish. This era is ending. Becoming a VMS platform and industry evangelist makes a company much, much harder to replace. This lock-in isn’t through predatory data practices or legal malarky, but through providing a product that is immensely more valuable than any of its peers. Multi-Product is the holy grail for software businesses. Acquiring customers is usually one of the most expensive aspects of building any software company. Selling multiple products to the same customer allows you to amortize that sales and marketing expense, expanding ARPU and TAM. It also can deepen the customer relationship, increasing net revenue retention and driving lifetime value. Further, in smaller markets, multi-product changes from a nice-to-have to a fundamentally necessary strategy for building a large business. It’s all about unit economics.

Actions express priorities and there is a reason the first Evergreen Funds, continuation vehicles and permanent capital vehicles are targeting VMS. For these truly phenomenal businesses, you don't want to get in the way of compounding. Their capital efficiency, durability, repeatable playbooks, and low churn are the things investors dream of.

if Bill has such a great ecosystem, why are their financials and fundamentals not that impressive? What companies would you avoid in the software industry? Is INTU one of them?

I own more VMS focussed once such as Constellation Software or Vitalhub, but also Servicenow. The later might be also not one of your favorites?